The summers are short and the winters long in the Arctic. Most foods were only available in the summertime and reserves had to be kept until the next spring. Iceland suffered a lack of firewood after most of the forests had been used up. This led to a salt shortage as distilling salt from sea requires a lot of fuel. Grain farming collapsed as the climate got colder and the import of meal was limited due to the country’s isolation.The gathering of food was highly seasonal and

many interesting traditions formed around this. What follows is a short account of what Icelandic nature has to offer. Those Icelanders who have lived abroad remember the excitement for the first cherries, the strawberry season when strawberries are eaten all day long, on bread and in desserts, people remember waiting for the apples and so on and so forth. This was also the case in Iceland but we have mostly forgotten all about it.

Spring in the old days

Numerous memoirs from the latter half of the 19th and through to the 20th century mention the excitement for the first cow to bear a calf. With it came ábrystir, a colostrum pudding and blood pudding, which in some regions was the first fresh food since the last year’s slaughtering season.

Lumpfish

Lumpfish arrived at the South Coast and in Breiðafjörður were it was speared along the coastline. Every part of it was used; livers were stuffed in the air bladders and caviar made from the roes. Flounder was plentiful in Breiðafjörður where it was usually dried, except in the fall when the fish was too fat and therefore salted instead.

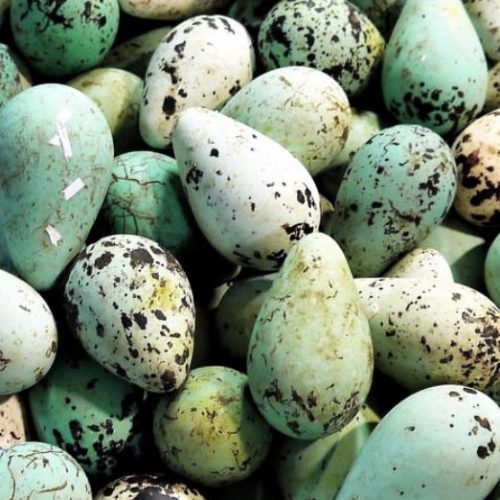

Gathering of eggs

Bird cliffs provided men with food throughout most of the year. The gathering of eggs began in spring. The way in which fresh eggs were consumed and processed varied from region to region. To name a few examples; they were preserved in ash or sand and boiled or pickled in some places. In other areas, fertilized eggs were allowed to rot and then eaten as cheese. The eggs were eaten fresh in Vestmannaeyjar and many people had no trouble finishing off 8 eggs in a single day.

Herbs and roots

Garden dock sprouted early and was harvested at the beginning of spring and was known as fardagakál (cabbage that was eaten during the days when men moved from farm to farm to work). It was considered perfect for making porridges and salads. A powerful medicinal tea was also brewed from the roots. Angelica was harvested during egg picking season as people wanted to get the stalks before they became stringy. Every part of the angelica was used, the roots were dug up using a specialized tool and stored in soil over winter while the stalks and leaves were pickled. The scurvy grass was picked before it bloomed. It was used in soups and porridges, bread and blood sausages with barley or rye. Cabbage roots were served with meat and they were eaten either raw or boiled. The reserves of sour whey where often depleted when spring rolled around, so people drank the brine of scurvy grass instead of whey. Dock was picked, chopped and eaten with boiled eggs or infused in butter and mixed with chopped hardboiled eggs. This dish can be found in all the fine foreign cookbooks from the 18th century but was an everyday dish around Iceland, especially in Dalir.

Seals

Seal grounds were visited and the catch was processed. This was mainly the job of women. Land seal pups were caught in nets in the spring and the Atlantic seal cubs were captured in mid-October when they were three weeks old. The processing varied by region. In Breiðafjörður, the meat of the seal pups was smoked without removing the fat. No other smoked and hanged meat tasted better. The heads were singed, like sheep heads and iron rods were inserted into the flippers and heated to singe the webbing. All the innards were taken, although the stomach was not eaten, as it could be used to contain liver oil or as a water wing for children.

Summer in the old days

Various herbs and vegetables were harvested when summer rolled around and were then either consumed immediately or pickled. The gathering of grasses and herbs began after egg season and before haying.

Iceland moss

Iceland moss is a lichen, which is a composite of algae and fungi. The fungi provide the lichen with water and minerals while the algae photosynthesize organic material. Iceland moss has been used in Iceland for centuries and was a common food in the past. Trips were made to the mountains, the herbs and grasses were pruned, dried and used in porridges but also to supplement meal in bread, blood sausages and milk. These trips were made again in the fall. This practice was most common in the North and East, as well as in the West Fjords. There are many accounts that tell of these trips and they provide a wealth of ideas for food tourism. Iceland moss is first mentioned in law books after 1300. It is possible that they did not become a staple of the Icelandic diet until meal and grain shortages plagued the nation.

The bird cliffs provided an abundance of food.

The cormorant is the first bird to lay eggs and the nestlings are fully grown around June – July, which is when they were hunted. The meat, which is fatty and delicious, was usually salted and smoked. Next in line was the black guillemot, its nestlings were fully grown in around July and August when the hunt took place. However, since this is also the time for haying, the black guillemot was not hunted in the islands, as it required hunters to make longer trips.

The puffin was the most hunted bird and the hunt began in the first week of August. Around Breiðafjörður the first puffin soup was anticipated with excitement. The puffin was boiled with scurvy grass and the first crop of potatoes and the soup was eaten standing up in the farmyard. This is a fun tradition that could be revived in Breiðafjörður.

The fulmar in Mýrdalur and Vestmannaeyjar was a foundation of the diet; the fulmar nestlings were usually hunted right before they became able to fly in mid-August. Food collecting from cliffs has created many exciting traditions worth reviving.

Fall in the old days

The scurvy grass was also harvested in the fall and made into cabbage soups and porridges and used as an ingredient in the food produced from innards. It was also pickled in barrels and the brine was also used as a drink. Around Breiðafjörður, where milk was not always available, brine was often made with scurvy grass.

Dulce

August was known as dulse month around the country, as the seaweed is best harvested during spring tide and St. John the Baptist’s Beheading day had one of the best tides of the year. During this time the dulse is still fully intact and filled with carbohydrates, having accumulated them over the summer. Along with the dulse, people also ate Iceland moss and false Irish moss to some extent, while seaweeds were rarely consumed.

Mushrooms

A wealth of mushrooms grows along the shrubberies, popping up in August and September. Mushrooms are not traditional food in Iceland, except in Skagafjörður, where they made soup from mushrooms boiled in whey. The timing of mushrooms blooming is ideal as it is after haying and before dulse picking. In the books Arnbjörg and Grasnytjar, Björn from Sauðlauksdal provides instructions for mushroom consumption recommending “boiling them and storing in acid. Thus, they are better and safer to eat than when they are fresh.” Mushrooms are one of Icelandic nature’s best-kept secrets.

Berries

August is also the time for berry-picking. Nine varieties of edible berries grow in Iceland: Bilberries, blueberries, crowberries, brambleberries, strawberries, rowanberries, bearberries, juniper berries and recently lingonberries have been discovered. The berries were eaten fresh or kept in skyr or acid for flavoring.

Slaughter season

Slaughter season began at the end of August and could last through October. It took significant efforts to process all the animals and every edible scrap was used and preserved. Food made from blood and innards was pickled or smoked.

Winter in the old days

Few fresh foods were available during the winter but those who could would slaughter a sheep for Christmas. Fulmar might be caught in the south, ptarmigan hunted in the northeast and trout fished through ice in Mývatn and other areas.