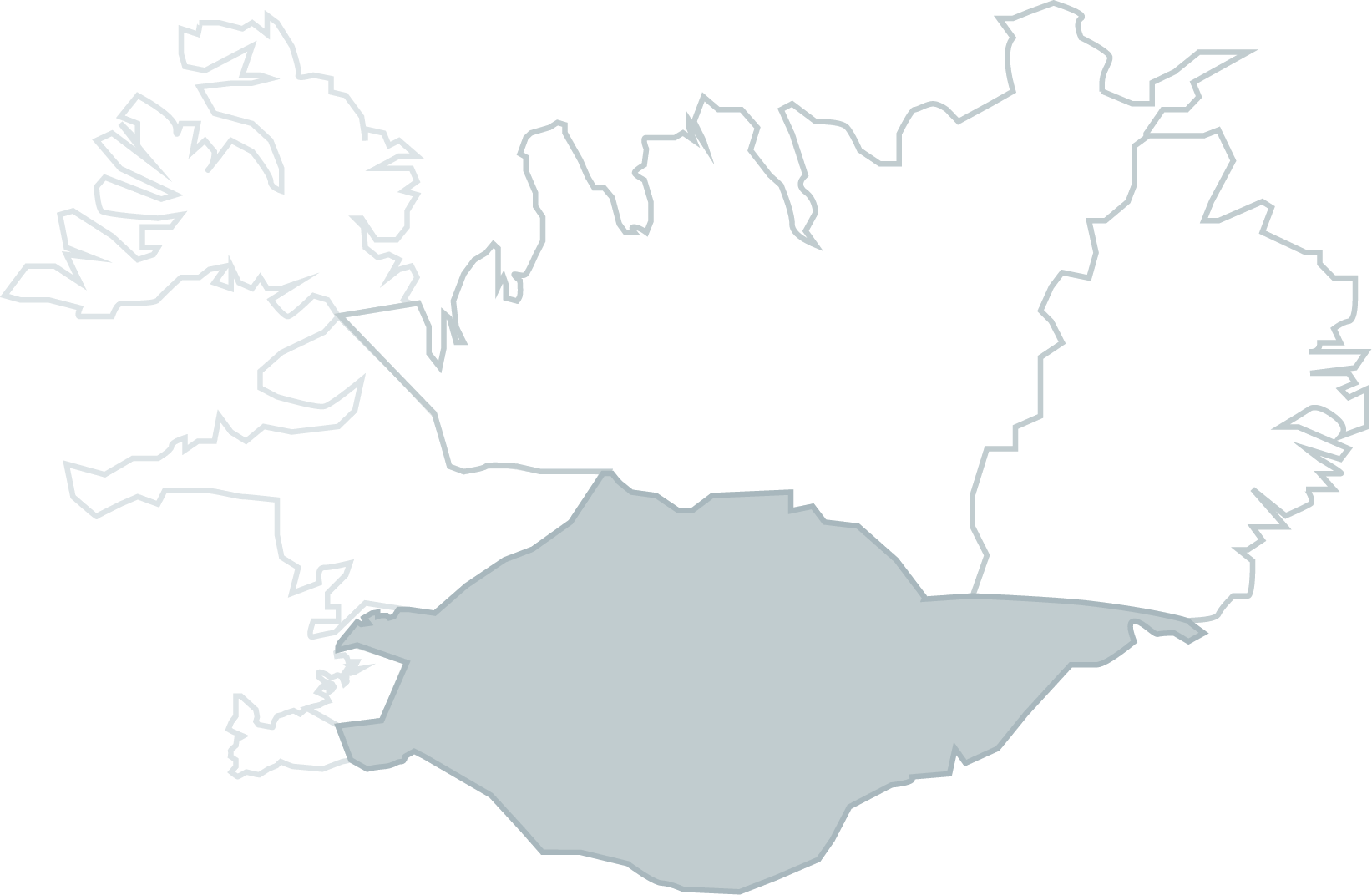

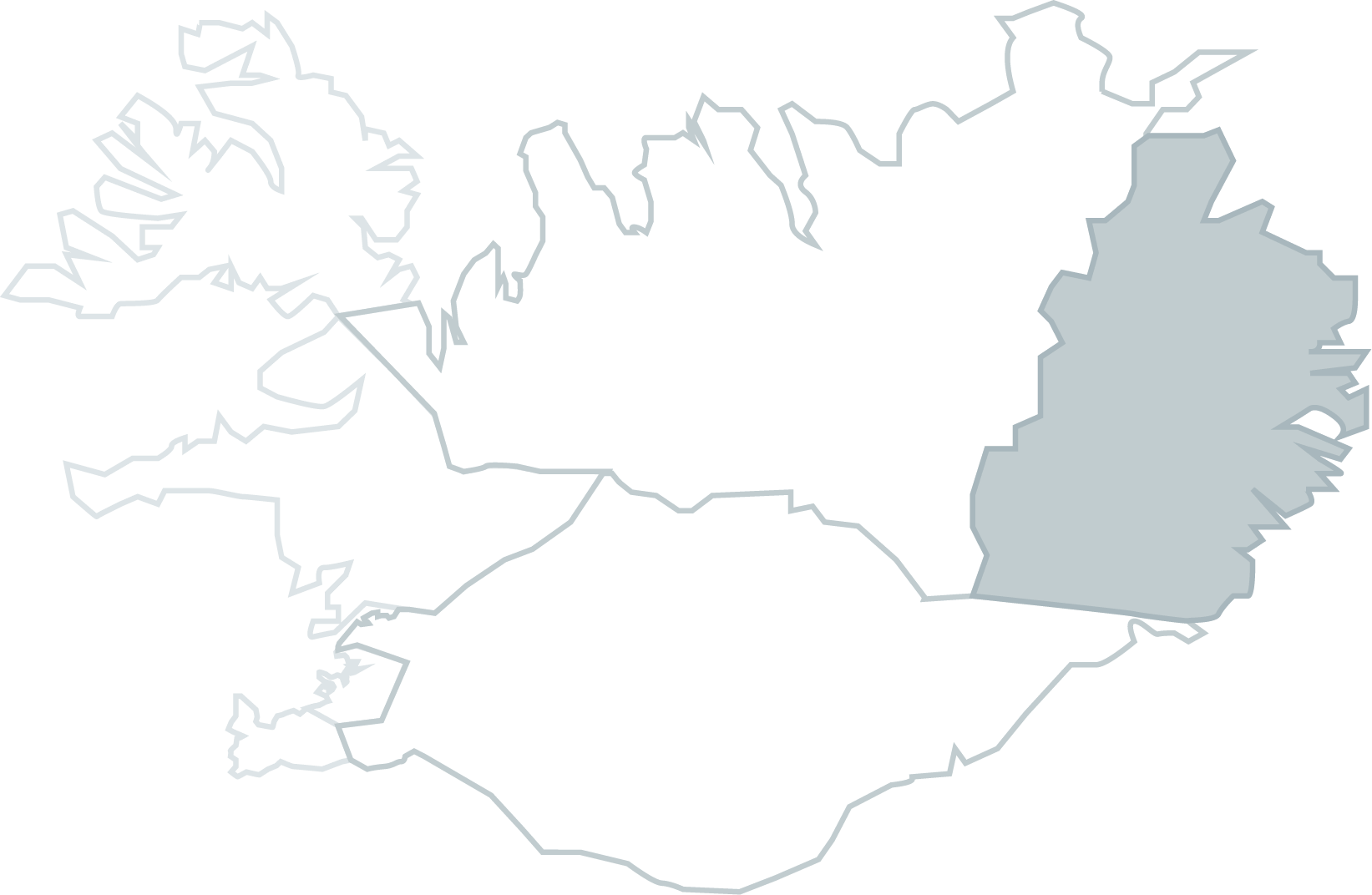

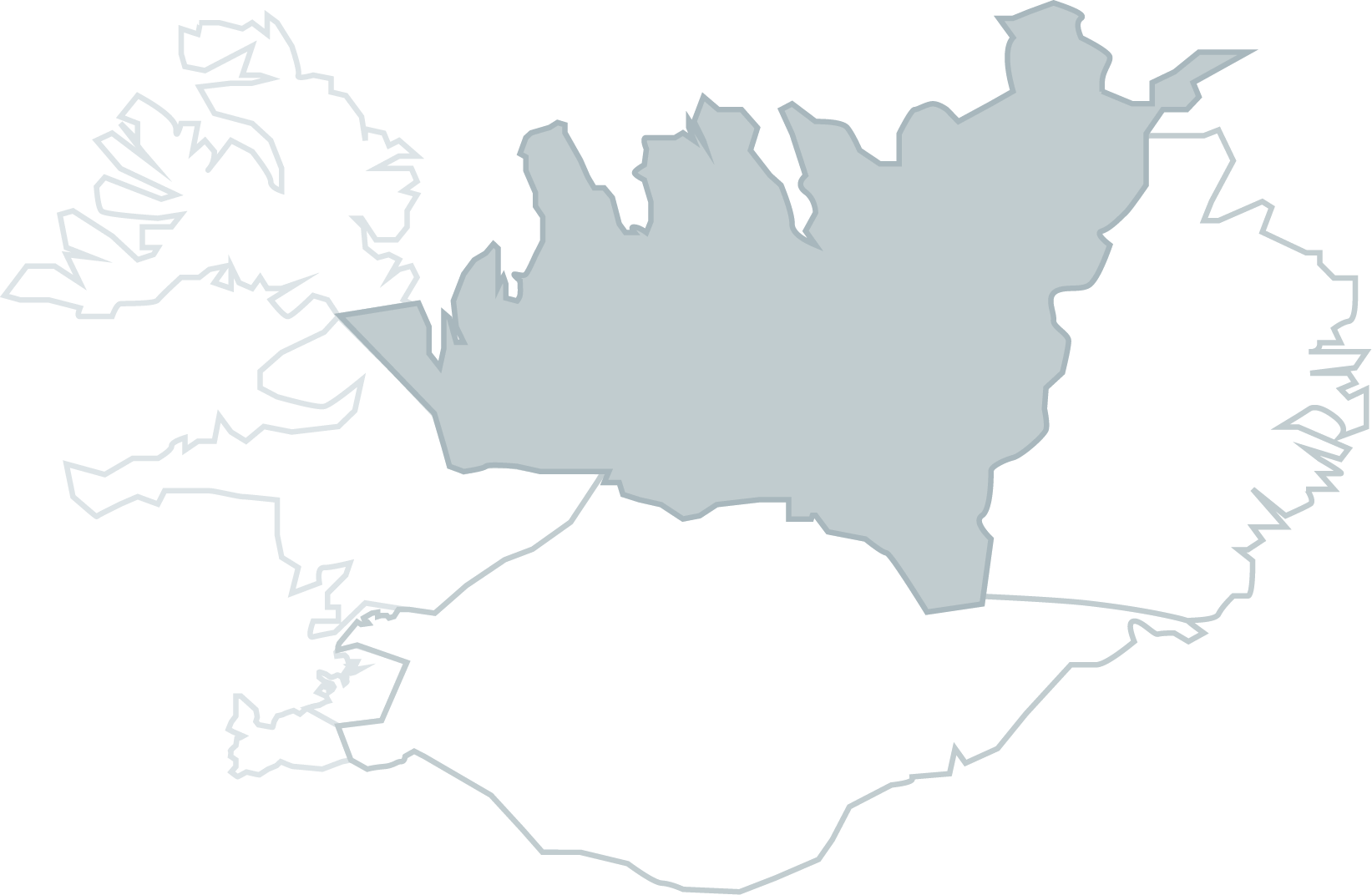

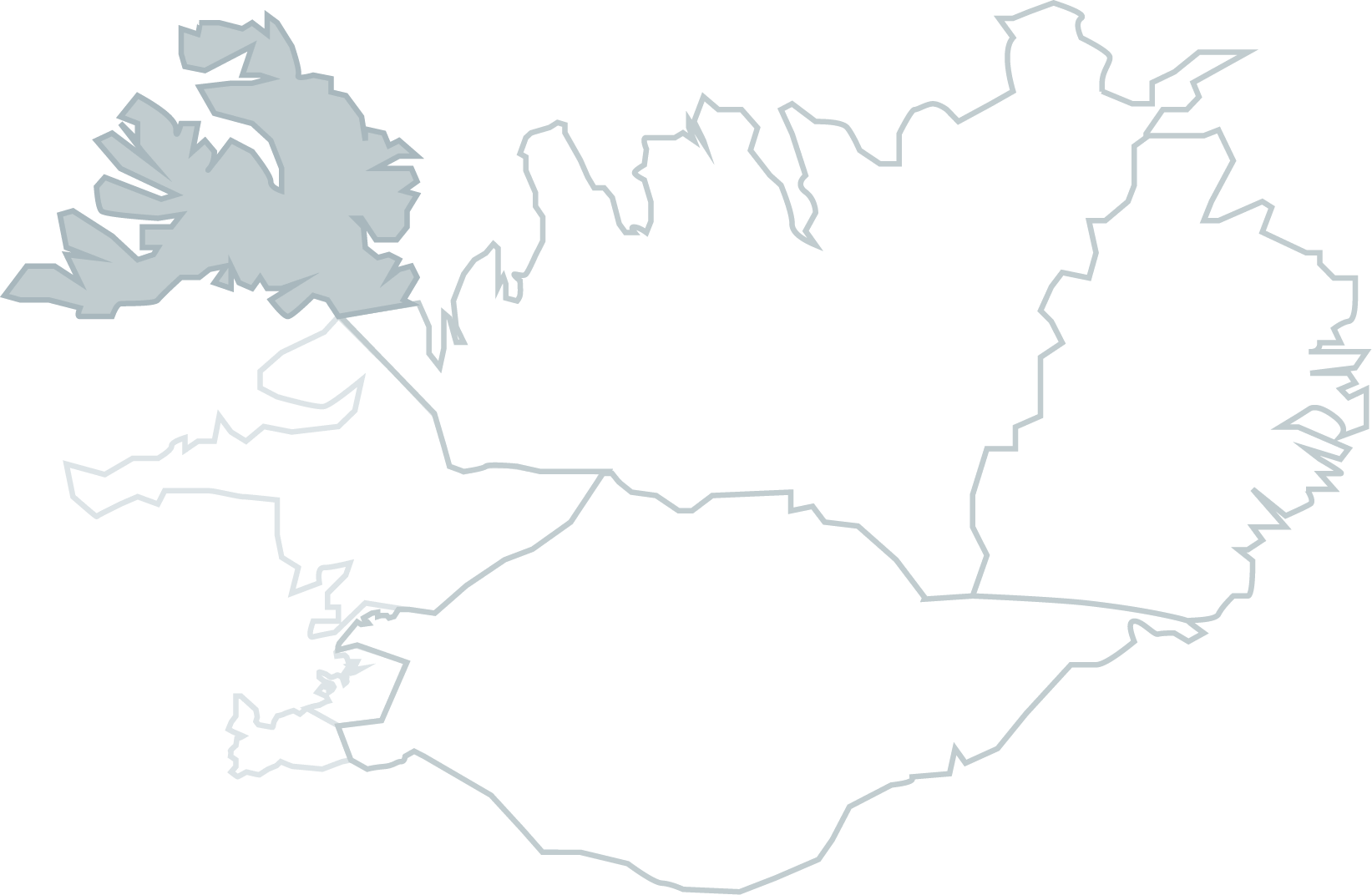

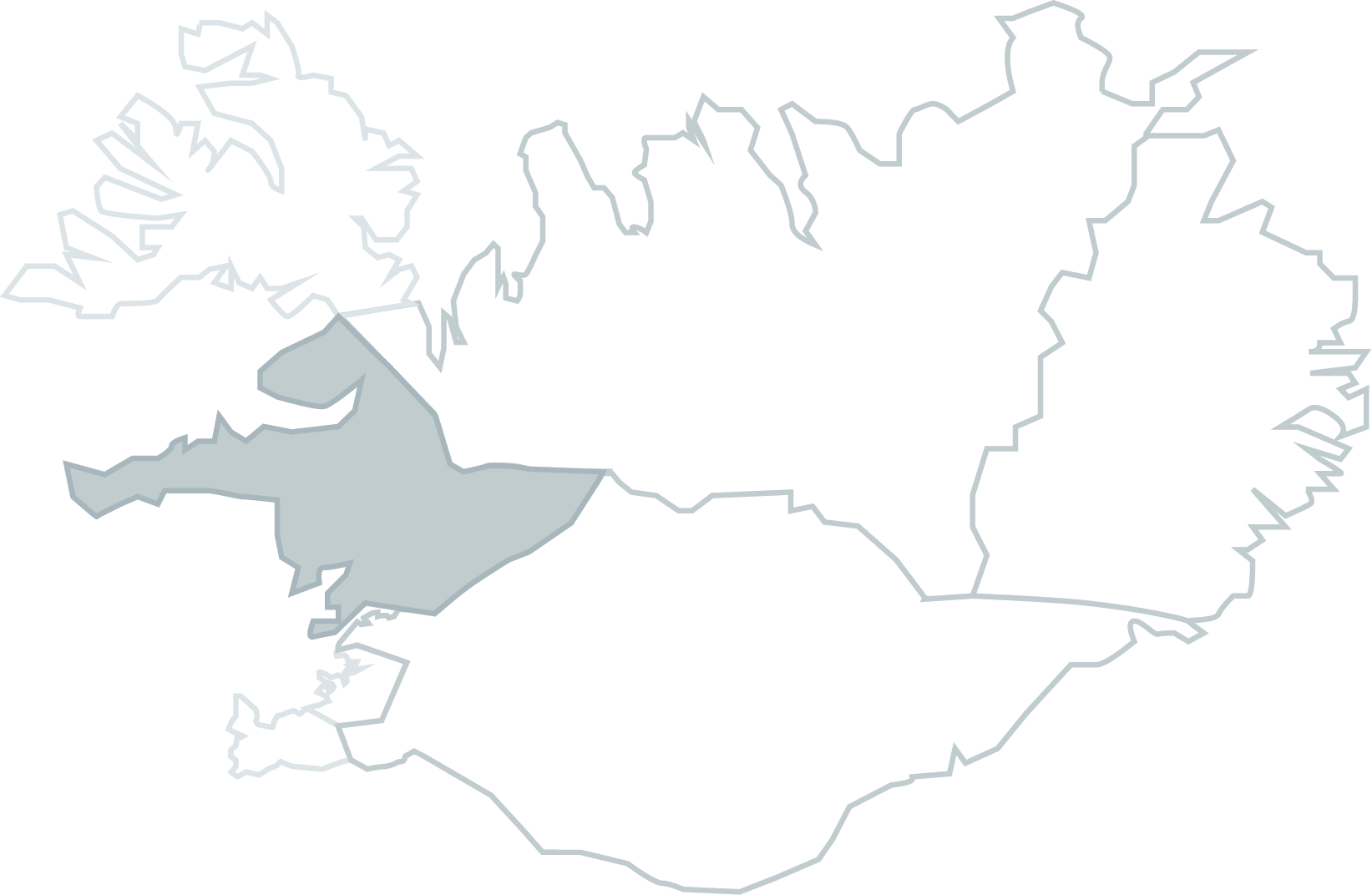

The South

The Southern lowlands, with their fertile soil and favorable weather conditions have been the center of food production in the 20th century. Dairy products are prominent and Iceland’s largest dairy is in Selfoss. Large meat production companies are also located in the area.

Through the ages, life in the region has been shaped by the extremes of nature. A tough habitat marked by glaciers, volcanoes and torrential glacial rivers, is mitigated only by the country’s most favorable weather conditions. Transportation was difficult in the past when unbridged glacial rivers had to be crossed. The glaciers in the north towered over the shallow coastline. Fishing was minimal for a great part of the region.

Garden & Herb Crops in Southern Iceland

Geothermal heat is essential to food production in Southern Iceland. The sustainable cultivation of vegetables, including tomatoes, cucumbers and peppers, in heated and illuminated greenhouses throughout the year has attracted attention. Mushrooms are grown in the South and there is a large potato production in Þykkvabær. The earliest evidence of an Icelander with an interest in potato farming points to Gísli Magnússon – Gísli the wise – a county magistrate in Rangárvellir. He was a pioneer in the field of gardening in 17th century Iceland. His interest in potatoes was like to have started during his years studying abroad. In 1670, Gísli asked his son Björn, who was studying in Denmark at the time, to send him English potatoes, but it is not certain whether any potatoes were sent or not. Múlakot, by Fljótshlíð, is the site of the oldest and most important private garden in Iceland. It was started in 1897 by Guðbjörg Þorleifsdóttir and is the site of a vegetable garden as well. The Maríubakki rutabaga – of the Kálfafell variety – is one of Iceland’s genetic treasures.

Caraway was first cultivated in Hlíðarendi. With the help of humans and animals, it has spread around the country. It has been used in bread making and as a spice in Brennivín, the Icelandic Aquavit. Sheriff Skúli transported caraway from Hlíðarendi to Viðey. Angelica grows wild in many places. In Mýrdalur they dug the roots up and kept in soil for the winter and then traded in amounts equaling those of grains and cereals. Angelica and garden dock stalks were eaten before they turned stringy. Several Icelandic products are based on the angelica.

Expansive barley fields and various cultivation experiments have taken place around Eyjafjöll – including the growing of rapeseed and wheat. Today you can buy Icelandic rapeseed oil for cooking and delicious oats. Archaeological excavations have turned up two examples of grain production in Iceland; at Bergþórshvoll and Gröf at Öræfi. From 1927 to 1967, an experimental farm was run at Sámsstaðir in Fljótshlíð, where they experimented with growing grains, among other things.

Smoked Sheep Belly, Paté & Milk Pudding

Oral accounts claim that horse meat was first consumed at Þykkvabær. The Development Fund of Southern Iceland recently supported a project at Þykkvabær aimed at developing horse “cracknels.” This is a traditional way of processing horsemeat where a fatty flank is cut into pieces and boiled. The product is then dried, resulting in delicious dried horse meat. Dried meat processing also takes place in other areas of the South. At Seglbúðir, south of Kirkjubæjarklaustur, there is an artisanal slaughterhouse specializing in sheep products. The meat is processed at the plant in Skaftártunga and sold fresh, smoked, dried and as cured sausages.

Both East and West Skaftafell counties have a unique culinary culture. Here the sea was particularly challenging while the nearest market town was far away and hard to reach. The trip, which was most often made to Eyrarbakki, could take up to three weeks. Preparations began as soon as the lambs were separated from their mothers in spring, the sheep were milked and cheese and butter made for those who made the trips. Spring brought eggs and colostrum while boiled milk was available in the fall. Beans cooked with pickled butter were a delicacy, as was rice pudding with raisins. Sheepbellies were boiled and laid in skyr and hung sausages were served on special occasions. Smálki, a kind of paté, was boiled straight into the sailor’s wooden bowls and topped with melted lard. Some of these dishes could easily be developed and adapted to modern taste!

A Long-Standing Dairy Tradition

Southern Iceland has a long and excellent history of making dairy products. The first creamery opened in 1903 and another in 1904. The creamary at Baugstaðir is now a museum opened to the public. It used to produce butter, cheese and other products made from cream. The butter was sold to England as “Danish Butter.” Today, the largest dairy is Mjólkursamsalan in Selfoss.

Half-Dried Fish & Freshly Boiled

Sea trout swims up the rivers. In the old days it was primarily eaten fresh, sometimes smoked but it was not suited for salting. Dried plaice or flounder replaced dried cod or haddock and this practice has recently been revived. Dried flounder is attractively packaged and sold at tourist attractions in the area. Through to the 20th century, children and teenagers were sent to the coastline to pick up the cod that had beached itself hunting capelin. Otherwise, people lived off half-dried fish, boiled fresh fish when available and roe cakes. The roe cakes were known across the country, the batter consists of roes and meal and they were boiled in whey. There is a land-based river trout farm in Fagridalur, close to Vík í Mýrdal. The farm uses cold water that comes from under the neighboring lava. Therefore, the river trout grows slower and consequently is less fatty.

Seals & Cliff Birds

In the eastern part of Southern Iceland, seals were hunted and the meat from the young harp seal and the pups in spring was considered the best. Seal fat was boiled with beans as a delicacy. Puffins were caught in pocket nets in Reynishverfi, Vík and Dyrhólaey and eaten fresh as well as salted. Beinastrjúgur, was made in Mýrdalur up until the 20th century. Bones from cod, livestock and birds were boiled until they became soft, then pickled and eaten with small breads.

The Arctic fulmar defines the cuisine of Mýrdalur. Fulmar is first mentioned in the area around 1820. Precise descriptions exist of the traditions and customs of fulmar hunting trips representing a treasure trove for tourism in this area and Vestmannaeyjar.

Every part of the fulmar was used. The eggs were gathered and eaten fresh; either boiled or in small pancakes. The heads, wings and legs were removed in a process known as pruning the bird. The head was eaten as a delicacy but it was hard to pluck and clean. Throughout the 20th century, the people of Mýrdalur were brought up eating fulmar at least twice a week.

In Vestmannaeyjar, eggs were collected every spring and fresh eggs were a welcome addition to the local diet after a winter of salted foods. Tasty fulmar and alcid eggs were the most sought after. These eggs are larger than normal chicken eggs; the fulmar eggs are white while the alcid eggs are green with black spots.

Every island was combed for eggs and fulmar eggs were easier to get to as they often make their nests in places reachable by foot. To get to the alcid’s eggs one needed to rappel down the sills where they make their nests.

Dulse & Carragheen

Dulse and carragheen were crucial components in the food of of East and West Skaftafell regions. The dulse was boiled in milk along with yellow turnips and eaten for either breakfast or lunch. It was also ground into porridges and bread, replacing half of the meal. Dulse and Iceland moss were purchased in Eyrarbakki where a hundredweight of dulse cost 20 salted fulmar nestlings. Iceland moss was half as valuable despite it serving the same purpose, costing only ten fulmar nestlings per hundredweight. Fulmar nestlings were still registered as a currency on the money market in the 20th century. Farmers in Mýrdalur did not possess a lot of land and for the feeding of a single sheep, they paid 25-30 fulmar nestlings. Scurvy grass and sea sandwort were used in porridges, soups, bread and food made from innards. Weedbread was made from 50% meal and 50% sea sandwort. Sea sandwort has an oily taste, so the dough was often flavored with caraway or angelica.

Katla Geopark and Local food

The Katla Geopark is located in Southern Iceland and spans three municipalities. Its purpose is for guests to be able to simultaneously experience the history, nature, culture and arts that define the area. This includes the local delicacies.

Numerous restaurants can be found in the south, many of which specialize in local ingredients, from geyser-baked bread to tasty tomato dishes and beverages. Hungry travelers can expect to find restaurants in repurposed houses.

For more information about culinary experiences see Visit South Iceland

Raw materials

-

Tomatoes, Cucumbers & Peppers

-

Pigs

-

Arctic Fulmar

-

Mushrooms

-

Potatoes

-

Rhubarb

-

Dulse, Seaweed, & Carragheen

-

Iceland Moss, Angelica, Berries, etc.

-

Beets, Carrots, Cauliflower, etc.

-

Ptarmigans, Ducks, & Geese

-

Dairy products

-

Whey, Ale & more

-

Barley, Wheat & Rye

-

Salmon & Trout

-

Fish

-

Seabirds

-

Fowl

-

Goats

-

Horses

-

Cattle

-

Sheep